In part 4 we’ve replaced Parallel.ForEach with Task. This allowed us run the processes on the ThreadPool threads, but waited only in the main thread. So the worker threads were never blocked on waits. They executed the child process, then processed the output callbacks and exited promptly. All the while, the main thread is waiting for everything to finish completely. To do this, we needed to both break the Run logic from the Wait. In addition, we had to keep the Process instances alive for the callbacks to work and we can detect the end correctly.

This worked well for us. Except for the nagging problem that we can’t use Parallel.ForEach. Or rather, if we did, even accidentally, we’d deadlock as we did before. Also, our wrapper isn’t readily reusable in other classes without explicitly separating the Run call from the Wait on separate threads as we did. Clearly this isn’t a bulletproof solution.

It might be tempting to think that the Process class is a thin wrapper around the OS process, but in fact it’s rather complex. It does a lot for us, and we shouldn’t throw it away. It’d be great if we could avoid the problem with ThreadPool altogether. Remember the reason we’re using it was because the synchronous version deadlocked as well.

What if we could improve the synchronous version?

Synchronous I/O Take 2

Recall that the deadlock happened because to read until the end of the output stream, we need to wait for the process to exit. The process, in its turn, wouldn’t exit until it has written all its output, which we’re reading. Since we’re reading only one stream at a time (either StandardOutput or StandardError,) if the buffer of the one we’re not reading gets full, we deadlock.

The solution would be to read a little from each. This would work, except for the little problem that if we read from a stream that doesn’t have data, we’d block until it gets data. This is exactly like the situation we were trying to avoid. A deadlock will happen when the other stream’s buffer is full, so the child process will block on writing to it, while we are waiting to read from the other stream that has no data yet.

Peek to the Rescue?

The Process class exposes both StandardOutput or StandardError streams, which have a Peek() function that returns the next character without removing it from the buffer. It returns -1 when we have no data to read, so we postpone reading until Peek() returns > -1.

Albeit, this won’t work. As many have pointed out, StreamReader.Peek can block! Which is ironic, considering that one would typically use it to poll the stream.

It seems we have no more hope in the synchronous world. We have no getters to query the available data as in NetworkStream.DataAvailable and length will throw an exception as it needs a seekable stream (which we haven’t). So we’re back to the Asynchronous world.

The Solution: No Solution!

I was almost sure I found an answer with direct access to the StandardOutput or StandardError streams. After all, these are just wrappers around the Win32 pipes. The async I/O in .Net is really a wrapper around the native Windows async infrastructure. So, in theory, we don’t need all the layers that Process and other class add on top of the raw interfaces. Asynchronous I/O in Windows works by passing an (typically manual-reset) event object and a callback function. All we really need is the event to get triggered. Lo and behold, we are also get a wait-handle in the IAsyncResult that BeginRead of Stream returns. So we could wait on it directly, as these are triggered by the FileSystem drivers, after issuing async reads like this:

var outAsyncRes = process.StandardOutput.BaseStream.BeginRead(outBuffer, 0, BUFFER_LEN, null, null);

var errAsyncRes = process.StandardError.BaseStream.BeginRead(errBuffer, 0, BUFFER_LEN, null, null);

var events = new[] { outAsyncRes.AsyncWaitHandle, errAsyncRes.AsyncWaitHandle };

WaitHandle.WaitAny(events, waitTimeMs);

Except, this wouldn’t work. There are two reasons why this doesn’t work, one blame goes to the OS and one to .Net.

Async Event Not Triggered by OS

The first issue is that Windows doesn’t always signal this even. You read that right. In fact, a comment in the FileStream code reads:

// Consider uncommenting this someday soon - the EventHandle

// in the Overlapped struct is really useless half of the

// time today since the OS doesn't signal it. [...]

True, the state of the event object is not changed if the operation finishes before the function returns.

.Net Callback Interop via ThreadPool

Because the event isn’t signaled in all cases, .Net needs to manually signal this event object when the Overlapped I/O callback is invoked. You’d think that would save the day. Albeit, the Overlapped I/O callback doesn’t call into managed code. The CLR handles such callbacks in a special way. In fact it knows about File I/O and .Net wrappers aren’t written in pure P/Invoke, but rather by support from the CLR as well as standard P/Invoke.

Because the system can’t invoke managed callbacks, the solution is for the CLR to do it itself. Of course this needs to be one in a responsive fashion, and without blocking all of CLR for each callback invocation What better solution than to queue a task on the ThreadPool that invokes the .Net callback? This callback will signal the event object we got in the IAsyncResult and, if set, it’ll call our delegate that we could pass to the BeginRead call.

So we’re back 180 degrees to ThreadPool and the original dilemma.

Conclusion

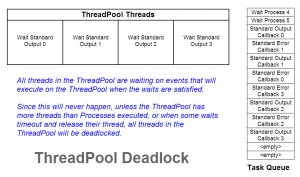

The task at hand seemed simple enough. Indeed, even after 5 posts, I still feel the frustration of not finding a generic solution that is both scalable and abstract. We’ve tried simple synchronous I/O, then switched to async, only to find that our waits can’t be satisfied because they are serviced by the worker threads that we are using to wait for the reads to complete. This took us to a polling strategy, that, once again, failed because the classes we are working with do not allow us to poll without blocking. The OS could have saved the day but because we’re in the belly of .Net, we have to play with its rules and that meant the OS callbacks had to be serviced on the same worker threads we are blocking. The ThreadPool is another stubbornly designed process-wide object that doesn’t allow us to gracefully and, more importantly, thread-safely, query and modify.

This means that we either need to explicitly use Tasks and the ProcessExecutor class we designed in the previous post or we need to roll our own internal thread pool to service the waits.

It is very easy to overlook a cyclic dependency such as this, especially in the wake of abstraction and separation of responsibilities. The complex nature of things was the perfect setup to overlook the subtle assumptions and expectations of each part of the code: the process spawning, the I/O readers, Parallel.ForEach and ultimately, the generic and omnipresent, ThreadPool.

The only hope for solving similar problems is to first find them. By incorrectly assuming (as I did) that any thread-safe function can be wrapped in Parallel.ForEach, and patting oneself for the marvels and simplicity of modern programming languages and for being proud of our silently-failing achievement, we only miss the opportunity to do so. By testing our code and verifying our assumptions, with skepticism and cynicism, rather than confidence and pride, do we stand a chance at finding out the sad truth, at least on the (hopefully) rare cases that we fail. Or abstraction fails, at any rate.

I can only wonder with a grin about other similar cases in the wild and how they are running slower than their brain-dead, one-at-a-time versions.